EH here. Alas, not being a coder, I don't know how to get the illustrations to show up on Ecosophia, so you may want to go to the source to read this.

Source: Ecosophia

Music as a Magical Language

Once again we have a month with five Wednesdays, and by time-honored custom I called on my readers to nominate and vote on their choice of topics for this post. This month, the relationship between occultism and music got the largest number of votes. It’s an intriguing topic, and one that has attracted a great deal of attention down through the years. It’s going to require a bit of explaining, though, so let’s get going.

We’ll have to start all the way back at the origins of Western occultism. Pythagoras, the first documented figure in the history of the Western occult tradition, taught his students about the occult side of music. The story has it that he was the one who first figured out the link between mathematics and music; more likely than not it was one of the things he picked up when he was studying the lore old Egypt under the tutelage of priests in the temples of the upper Nile valley, but he was certainly the one who launched that knowledge into the Greek world, whence it came by various roundabout ways to us.

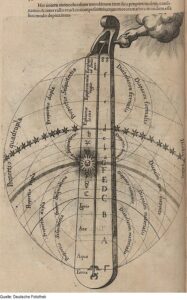

You’ll find plenty of comparable material in the great occult syntheses of the Renaissance. The image below on the right has been reprinted fairly often over the last century or so, mostly by people who don’t know what it means. It’s a diagram from one of the occult encyclopedias of Robert Fludd, who assembled most of the lore of Renaissance occultism into gorgeously illustrated books in the first half of the seventeenth century. Those lines and Latin words are meant to suggest that the entire structure of the cosmos is arranged like the frets on a musical instrument, descending the scale from the tuning peg turned by a divine hand to the bridge down there at the bottom, which is the world we inhabit.

The instrument is called a monochord. It’s a single string stretched over a fretboard, a little like a one-string mountain dulcimer, and it was the standard way to learn music theory until modern times. You took your monochord, a strip of paper, and the usual tools of geometry; you divided the strip at certain intervals, and pressed your finger down at those divisions, and lo and behold, you had a musical scale. You then did a different construction and ended up with a different scale. Rinse and repeat, and you had a good grasp of the way that notes are extracted from the continuum of sound, and some sense of the subtle variations in tuning that were standard in Western music until the end of the Baroque era.

Our music doesn’t use those subtle variations any more. Late in the eighteeenth century the old scales with their differing values were standardized into the current equal-tempered scale of Western music, which plays every key more or less well enough to pass but gets none of them quite right. There’s a reason for that, and it goes all the way back to the Greek colonial city of Crotona. That was where Pythagoras lectured to students eager to learn the wisdom of Egypt, for all the world like some newly minted guru at the end of the 1960s sitting in Central Park with a circle of eager hippies sitting around him.

It was Pythagoras who introduced to the Western world the idea that numbers expressed the secret code behind reality. The scientists who act as though nothing is real unless it can be counted or quantified? All unknowing, they’re channeling the mystic guru of Crotona. His original teachings apparently held that every relationship in the material world could be understood as a relationship between two or more natural numbers. (1, 2, 3, and so on are the natural numbers.) His musical teachings were an important bit of evidence for that, because the basic intervals of music do in fact work out to ratios between natural numbers: measured in string lengths or the like, 1 to 2 gives you the octave, 2 to 3 gives you the perfect fifth, and 3 to 4 gives you the perfect fourth.

The trouble creeps in if you try to go up or down this kind of scale very far. No matter which of the old scales you use, if you construct them using a monochord or some equivalent method using geometry, and take it more than a few octaves, the high notes and the low ones will end up clashing with each other. That’s what Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier was about. In his time you had to retune the strings of every keyboard instrument any time you changed key, to avoid the discords between high and low notes. The pieces in The Well-Tempered Clavier allowed you to check your keyboard to make sure it was properly tuned—of course, being Bach, they were also musical masterpieces, but they also had the practical function of avoiding the problems with tempered scales. They only went so far, however; beyond that, no matter what, you’re in trouble.

It’s one form of a general problem that afflicts all the ancient mathematical sciences—the problem of incommensurability. In an important sense, Pythagoras was wrong: there are ratios, important ones, that can’t be expressed by any ratio between natural numbers at all. π, the ratio between a circle’s diameter and its circumference, is one of these. √2, the ratio between the side of a square and its diagonal, is another. In astronomy and astrology (which counted as a single science in Pythagoras’s time), the mismatch between the solar year and the lunar month is another good example; there’s no way to make the relationship come out exactly. Octaves and fifths, finally, are incommensurable; the mismatch is subtle as long as you stay within a narrow range of a few octaves, but it’s there.

The Pythagoreans figured this out late in the life of their teacher. For a while it was one of their big secrets; several ancient sources claimed that the first initiate who let the secret out was shoved off a ship and drowned in the middle of the Mediterranean as he fled from Crotona. (Yes, my brother Masons, this was the Pythagoreans’ Captain Morgan incident.) Word got out anyway. Eventually—certainly by the Renaissance, probably well before then – the incommensurable ratios in geometry, music, and astronomy turned into ways to talk about the ways that spirit transcends human rationality. That turned tempering schemes into a meditation, as well as an excuse for Bach to create some fine music.

The problem in the eighteenth century is that composers and listeners alike wanted to reach out past the limits of a few octaves, and they wanted music that modulated from key to key in the middle of a single piece of music. They wanted keyboards that went as far to both sides as a musician could reach; they wanted string quartets with violins and cellos playing together, and orchestras with flutes and tubas playing together, all veering from key to key at will. You can’t do that with any of the old scales, because the high keys and the low ones, and the high instruments and the low ones, will end up producing discords; even in the middle, your tempered scale will only work in one key, and then everyone has to retune. So the modern system of equal temperament was invented. It squeezed nearly every note in the octave out of its proper place, so that everything would harmonize more or less.

The entire world of post-Baroque classical music was made possible by that change. The piano, with its 88 keys, its massive steel frame, and its array of strings under high tension, required it; nearly all classical music depends on it; the notes that John Williams used so memorably in the theme of Star Wars, and the rest of the panoply of music that fills our entertainment media, can’t get by without it. Nonetheless, unless you happen to have taken in some early music by performers who use the old tempered scales, there are worlds of music you’ll never experience. As with so much in the modern industrial world, we traded a very wide range of possibilities for a much narrower one that allowed us to go very far in one direction.

Does this mean that the equal-tempered scale is wrong, and that we all ought to go back to Baroque scales? You can find plenty of people in certain corners of the Western esoteric scene who insist on this. I’d argue that they’re missing the point. To understand things a little better, let’s go back to the monochord.

It’s an educational experience to make or purchase a monochord—I’ve done both—and use it to construct a scale using any of the standard ancient, medieval, or Renaissance methods. Better still, use it to construct several such scales, and use each scale to tune some stringed instrument—one of those little fifteen-stringed lap psalteries that children are taught to play on is as good as anything else. Play some familiar tunes in each of the different tunings, and notice how the flavor of the notes changes. Do this a few times, or more than a few times, and you’ll discover something of great importance that many people never realize: musical sound is a continuum, which is divided more or less arbitrarily into distinct notes.

If you want to see this realization taken to its logical extreme, listen to some classical Indian music, or any of the other musical traditions around the world where microtonal tunings are used. Classical Indian music has thousands of different tunings, which are called ragas. Each raga has certain melodies that are traditionally played in it; certain ragas are considered appropriate for different moods, times of day, and so on. It’s the logic of The Well-Tempered Clavier taken further than Bach ever dreamed of taking it. The results are impressively beautiful, but it’s a beauty that most Westerners have to learn to appreciate.

The same is true of the Asian musical tradition that produced the piece linked here. Turn up the speakers on your computer and get that playing before you read on.

That’s a piece of gagaku music. Gagaku—the word can be translated “correct music” or “elegant music”—is the oldest surviving Japanese musical tradition. It was partly borrowed from, and party inspired by, the music of the imperial Chinese court in the Tang dynasty: say, around 600 AD. To Japanese listeners, it has something like the same archaic ambience that Gregorian chant has to Western ears. To most Western listeners, once those high shrill buzzing reed instruments come in—wait for it—it has something like the ambience of a chorus of dental drills. It doesn’t use our scale, or anything like it; it uses a series of pentatonic modes—that is to say, six notes to the octave rather than eight, variously arranged.

My motive in having you play this isn’t a desire to torture my readers, though some may argue with this claim of mine. The point to this exercise in unfamiliar music is to get past a certain pervasive bad habit in modern books on the occult dimensions of music: the notion that music—meaning our kind of music, post-eighteenth century Western music using an equally tempered scale—is a “universal language.” It’s not. When it was first introduced to people outside the Western countries, most of them thought it was as bizarre as you probably find gagaku. Many of them are used to it now, for the same reason that you can find someone who speaks English in a really remarkable range of countries all over the world, but there’s nothing inherently universal about our idiosyncratic Western music.

Western music itself has gone through a whole series of convulsions in its history, driving and driven by sharp changes in what counted as music. The medieval church insisted that the only good music was theirs, and followed strict rules that forbade certain scales from being played—today’s major scale, the one that most people who aren’t musicians think of as the musical scale, was condemned as the modus lascivius or “lustful mode.” Come the Renaissance, the medieval modes got chopped up and replaced by seven planetary modes, in which the Ionian mode (our major scale) was quite sensibly assigned to Venus, and the Aeolian mode (our natural minor scale) was given to the Moon. The odd sad flavor of Appalachian folk music? That’s because the mountain folk preserved one of the others, the Mixolydian mode, which belongs to Saturn.

Then five of the modes got cast aside as Renaissance music gave way to Baroque, leaving the Ionian mode to become the major scale and the Aeolian mode to be wrenched out of shape into the harmonic minor: another narrowing of options to allow maximum extension in one direction. Then came equal temperament, a plethora of new musical instruments, and the golden age of classical music soared to its completion in the early twentieth century before it ran hard into the limits of its own creative space. (Every artistic tradition does this sooner or later.) Afterwards, elements of Western classical music got picked up and reworked for other musical dialects—jazz, for example, was what happened when African-American blues music picked up some of the possibilities of the classical language and started doing astonishing new things with them.

The comparison with language is useful. Languages around the world vary quite a bit in the sounds they use, the way those sounds are assembled into words, and the way those words express meaning when assembled into utterances in speech or on the written page. People who only know one language have no clue just how wildly diverse human languages are. There are languages in which words are divided grammatically between wet and dry; there are languages in which prepositions (in English, these are words like “in” and “over” and “near”) change depending on person and number, like verbs in Spanish. There are languages in which “I go wherever there is dancing” is a single word. There are words in some languages you can’t spell correctly with the English alphabet no matter what, because we don’t have letters for some of the sounds those languages use.

Exactly the same sort of diversity is true of music. What passes for “world music” these days has generally had all the sharp corners filed off to make it an easily digestible commodity for bored Americans; if you get outside of that musical ghetto, you’ll find a much more confusing and interesting world. Go listen to some Indonesian gamelan, or some classical Indian music, or some of the Celtic music that hasn’t had its gonads chopped off to make it appeal to the bland middle ground of taste—Breton bagpipe music is a good place to start—or some Middle Eastern or African or—well, the list goes on. There’s an entire world of musical languages out there. None of them are more universal than any other, any more than Hindi is more universal than Spanish or Korean is more universal than Swahili.

All this has to be grasped, in turn, if we’re to make sense of the occult dimensions of music. If you grew up within a culture’s musical tradition, you’ll have emotional and cognitive responses to music composed and performed in that tradition, just as if you grew up speaking a certain language you’ll have emotional and cognitive responses to words and sentences in that language—that’s what gives poetry and fiction their power. If you take the time to learn a musical tradition or a language you didn’t grow up with, you might be able to get to the same level of responsiveness in that music or language, too—though it will take time and practice.

Can you use those responses to cause changes in consciousness in accordance with will? You bet. That’s why soldiers used to march into battle to the music of fife and drum—to young men from Western countries, raised in our musical traditions, the high shrill notes of the fife have a potent effect on the mind and will. (The ancient Greeks also had flute players accompanying them into battle, so this may be one of Western cultures’ inheritances from classical times.) That’s why romantic music is romantic and why rock music has the reputation it has as a means of getting laid. Music is powerful stuff, just as language is.

That’s why, in turn, I know quite a few practitioners of planetary magic who like to play bits from Holst’s The Planets before doing a planetary invocation. Holst was a student of astrology and occultism; he’s known to have studied the work of British astrologer Alan Leo (real name Frederick William Allen) while working on that symphony, and you can tell—each of the planets gets a musical theme that expresses its energy and character extremely well. He knew exactly what he was doing: the Mars section, which is playing on my CD player as I write this, was composed in 5/4 time to catch the planet’s traditional fivefold energy. I’ve used it myself for magical purposes, with excellent results.

Is it the only option? Of course not. I don’t happen to know Indian classical music well enough to give examples, but I’d be amazed if there weren’t ragas suitable for every planet and every one of the elemental tattwas into the bargain—and it wouldn’t surprise me in the least if such ragas were used systematically in ritual and spiritual practice. For that matter, it wouldn’t be too hard to work out classic rock numbers for every planet and element—just for starters, how about Fleetwood Mac’s “Rhiannon” for the Moon, and Blue Öyster Cult’s “Don’t Fear The Reaper” for Saturn? Jazz, folk, C&W, metal? I’ll leave those for serious fans of those genres, but I know of no reason why those couldn’t be used with good effect too.

The point of all of this, as I hope my readers have grasped now, is that there is no one rule that all music must follow to count as magical. There is no one universal language of music; what there is, instead, is a world of different musical languages, any one of which can have magical effects in the most literal sense of that phrase if you use it with that intention. Whatever kind of music inspires and energizes you, it’s a safe bet that it can inspire and energize your magical ceremonies and occult practices. That’s as true of the Western classical music that I love as it is of any other tradition; it’s also true, by the way, of the older Western music that some traditionalists insist is the only valid music. (It’s not the only valid music, but it’s as valid as any other.) Occultism is a living and growing tradition, not a mummified corpse. Try including music with your rituals, your meditations, your divinations, your prayers; see what effects you get, and go from there.

No comments:

Post a Comment