Source: Consortium News

DIANA JOHNSTONE: D-Day 2024

In retrospect, it becomes clear that the Cold War “communist threat” was only a pretext for great powers seeking more power.

The British Normandy World War II Memorial in Ver-su-Mer, Normandy, France, June 6, 2024. (Number 10 Downing, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

By Diana Johnstone

Special to Consortium News

Ceremonies were held last week commemorating the 80th anniversary of Operation Overlord, the Anglo-American landing on the beaches of Normandy that took place on June 6, 1944, known as D-Day. For the very first time, the Russians were ostentatiously not invited to take part in the ceremonies.

Ceremonies were held last week commemorating the 80th anniversary of Operation Overlord, the Anglo-American landing on the beaches of Normandy that took place on June 6, 1944, known as D-Day. For the very first time, the Russians were ostentatiously not invited to take part in the ceremonies.

The Russian absence symbolically altered the meaning of the festivities. Certainly the significance of Operation Overlord as the first step in the domination of Western Europe by the English-speaking world was more pertinent than ever. But without Russia, the event was symbolically taken out of the original context of World War II.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky was invited to give a video address to the French Parliament in honor of the occasion. Zelensky pulled out all the rhetorical stops to demonize Vladimir Putin, describing the Russian president as the “common enemy” of Ukraine and Europe.

Russia, he claimed “is a territory where life no longer has any value… It’s the opposite of Europe, it’s the anti-Europe.”

So after 80 years, D-Day symbolically celebrated a different alliance and a different war — or perhaps, the same old war, but with the attempt to change the ending.

Here was a shift in alliances which would have pleased a good part of the pre-war, British upper class. From the time he took power, Adolf Hitler had many admirers in Britain’s aristocracy and even in its royal family. Many saw Hitler as the effective antidote to Russian “judeo-bolshevism.”

At the end of the war, there were those who would have favored “finishing the job” by turning against Russia. It has taken 80 years to make it happen. But the seeds of the reversal were always there.

D-Day & the Russians

Soviet and Polish Armia Krajowa soldiers in Vilnius, July 1944. (Polish National Archive/Wikimedia Commons/Public domain)

In June 1941, without so much as a pretext or false flag, Nazi Germany massively invaded the Soviet Union. In December, the United States was brought into the war by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

As the war raged on the Eastern front, Moscow pleaded with its Western allies, the U.S. and Britain, to open a second front in order to divide German forces. By the time the Western Allies landed in Normandy, the Red Army had already decisively defeated the Nazi invaders in Russia and was on the verge of opening a gigantic front in Soviet Belarus that dwarfed the Normandy battle.

The Red Army launched Operation Bagration on June 22, 1944, and by Aug. 19 had destroyed 28 of 34 divisions, completely shattering the German front line. It was the biggest defeat in German military history, with around 450,000 German casualties. After liberating Minsk, the Red Army advanced on to victories in Lithuania, Poland and Romania.

[See: The D-Day of the Eastern Front]

The Red Army offensive in the East undoubtedly ensured the success of the Anglo-American-Canadian Allied forces against much weaker German forces in Normandy.

D-Day & the French

As decided by the Anglo-Americans, the only role for the French in Operation Overlord was that of civilian casualties. In preparation for the landings, British and American bombers pounded French railway towns and seaports, causing massive destruction and tens of thousands of French civilian casualties.

In the course of operations in Normandy, numerous villages, the town of St Lô and the city of Caen were destroyed by Anglo-American aviation.

The Free French armed forces under the supreme command of General Charles de Gaulle were deliberately excluded from taking part in Operation Overlord. De Gaulle recalled to his biographer Alain Peyrefitte how he was informed by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill:

“Churchill summoned me to London on June 4, like a squire summoning his butler. And he told me about the landings, without any French unit having been scheduled to take part. I criticized him for taking orders from Roosevelt, instead of imposing a European will on him. He then shouted at me with all the force of his lungs: ‘De Gaulle, you must understand that when I have to choose between you and Roosevelt, I’ll always prefer Roosevelt. When we have to choose between the French and the Americans, we’ll always prefer the Americans.’”

As a result, De Gaulle adamantly refused to take part in D-Day memorial ceremonies.

“The June 6th landings were an Anglo-Saxon affair, from which France was excluded. They were determined to set themselves up in France as if it were enemy territory! Just as they had just done in Italy and were about to do in Germany! … . And you want me to go and commemorate their landing, when it was the prelude to a second occupation of the country? No, no, don’t count on me!”

Excluded from the Normandy operation, in August the Free French First Army joined the Allied invasion of Southern France.

The Americans had made plans to impose a military government on France, through AMGOT (Allied Military Government of Occupied Territories).

This was avoided by the stubbornness of de Gaulle, who ordered the Resistance to restore independent political structures throughout France, and who succeeded in persuading supreme Allied Commander General Dwight Eisenhower to allow Free French forces and a Resistance uprising to liberate Paris in late August 1944.

De Gaulle and entourage on the Champs Élysées following the city’s liberation on Aug. 26, 1944. (Imperial War Museums, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

D-Day in Hollywood

France has always celebrated the Normandy landing as a liberation. Polls show, however, that views of its significance have evolved over the decades. Soon after the end of the war, public opinion was grateful to the Anglo-Americans but overwhelmingly attributed the final victory in World War II to the Red Army.

Increasingly, opinion has shifted to the idea that D-Day was the decisive battle and that the war was won primarily by the Americans with help from the British. This evolution can be largely credited to Hollywood.

The Marshall Plan and French indebtedness provided the context for post-war commercial deals with both financial and political aspects.

On May 28, 1946, U.S. Secretary of State James Byrnes and French representative Léon Blum signed a deal concerning motion pictures. The Blum-Byrnes agreement stipulated that French movie theaters were required to show French-made films for only four out of every 13 weeks, while the remaining nine weeks were open to foreign competition, in practice mostly filled by American productions.

Hollywood had a huge backlog, already amortized on the home market and thus cheap. As a result, in the first half of 1947, 340 American films were shown compared to 40 French ones.

France reaped financial benefits from this deal in the form of credits, but the flood of Hollywood productions contributed heavily to a cultural Americanization, influencing both “the way of life” and historic realities.

The Normandy landing was indeed a dramatic battle suitable to be portrayed in many movies. However, the cinematic focus on D-Day has inevitably fostered the widespread impression that the United States rather than the Soviet Union defeated Nazi Germany.

Alliance Reversal No. 1 – The British

Britain’s King Charles and the queen at a D-Day commemoration in Portsmouth, U.K., on June 5. (No 10 Downing, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

By June 1944, with the Red Army well on the way to decisively defeating the Wehrmacht, Operation Overlord was hailed by Soviet leaders as a helpful second front. For Anglo-American strategists, it was also a way to block the Soviet Westward advance.

British leaders, and Churchill in particular, actually contemplated moving Eastward against the Red Army once the Wehrmacht was defeated.

It must be recalled that in the 19th century, British imperialists saw Russia as a potential threat to its rule over India and further expansion in Central Asia, and developed strategic planning based on the concept of Russia as its principal enemy on the Eurasian continent. This attitude persisted.

At the very moment of Germany’s defeat in May 1945, Churchill ordered the British Armed Forces’ Joint Planning Staff to develop plans for a surprise Anglo-American attack on the forces of their Soviet ally in Germany.

Top-secret until 1998, the plans even included arming defeated Wehrmacht and SS troops to take part. This fantasy was code-named Operation Unthinkable, which coincides with the judgment of the British chiefs of staff, who rejected it as out of the question.

At the February Yalta meeting just three months earlier, Churchill had praised Soviet leader Joseph Stalin as “a friend whom we can trust.” The reverse was certainly not true. One might assume that Franklin D. Roosevelt would have dismissed any such plans had he not died in April.

Roosevelt seemed confident that the war-exhausted Soviet Union was no threat to the United States, which was indeed true.

Seated from left: Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin at the Yalta Conference in 1945. (Wikimedia Commons/Public domain)

In fact, Stalin always scrupulously respected the sphere of influence agreements with the Western allies, refusing to support the communist liberation movement in Greece (which angered Josip Broz Tito, contributing to Moscow’s split with Yugoslavia) and consistently urged the strong Communist Parties in Italy and France to go easy in their political demands. While those parties were treated as dangerous threats by the right, they were fiercely opposed by ultra-leftists for staying within the system rather than pursuing revolution.

Soviet and Russian leaders truly wanted peace with their erstwhile Western allies and never had any ambition to control the entire continent. They understood the Yalta agreement as authorizing their insistence on imposing a defensive buffer zone on the string of Eastern European States liberated from Nazi control by the Red Army.

Russia had undergone more than one devastating invasion from the West. It responded with a repressive defensiveness which the Atlantic powers, intent on access everywhere, saw as potentially aggressive.

The Soviet clampdown on their satellites only hardened in response to the Western challenge eloquently announced by Winston Churchill 10 months after the end of the war. The spark was lit to a dynamic of endless and futile hostility.

Churchill was voted out of office by a Labour Party landslide in July 1945. But his influence as wartime leader remained overwhelming in the United States. On March 6, 1946, Churchill gave an historic speech at a small college in Missouri, the home state of Roosevelt’s inexperienced and influenceable successor, Harry Truman.

The speech was meant to renew the wartime Anglo-American alliance – this time against the third great wartime ally, Soviet Russia.

Churchill titled his speech, “Sinews of Peace.” In reality, it announced the Cold War in the historic phrase: “From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the Continent.”

The Iron Curtain designated the Soviet sphere, essentially defensive and static. The problem for Churchill was the loss of influence in that part of the world. A curtain, even if “iron,” is essentially defensive, but his words, were picked up as warning of a threat.

“Nobody knows what Soviet Russia and its Communist international organisation intends to do in the immediate future, or what are the limits, if any, to their expansive and proselytising tendencies.” (This despite the fact that Stalin had dissolved the Communist International on May 15, 1943.)

In America, this uncertainty was soon transformed into a ubiquitous “communist threat” that needed to be hunted down and eradicated in the State Department, trade unions and Hollywood.

Alliance Reversal No. 2: The Americans

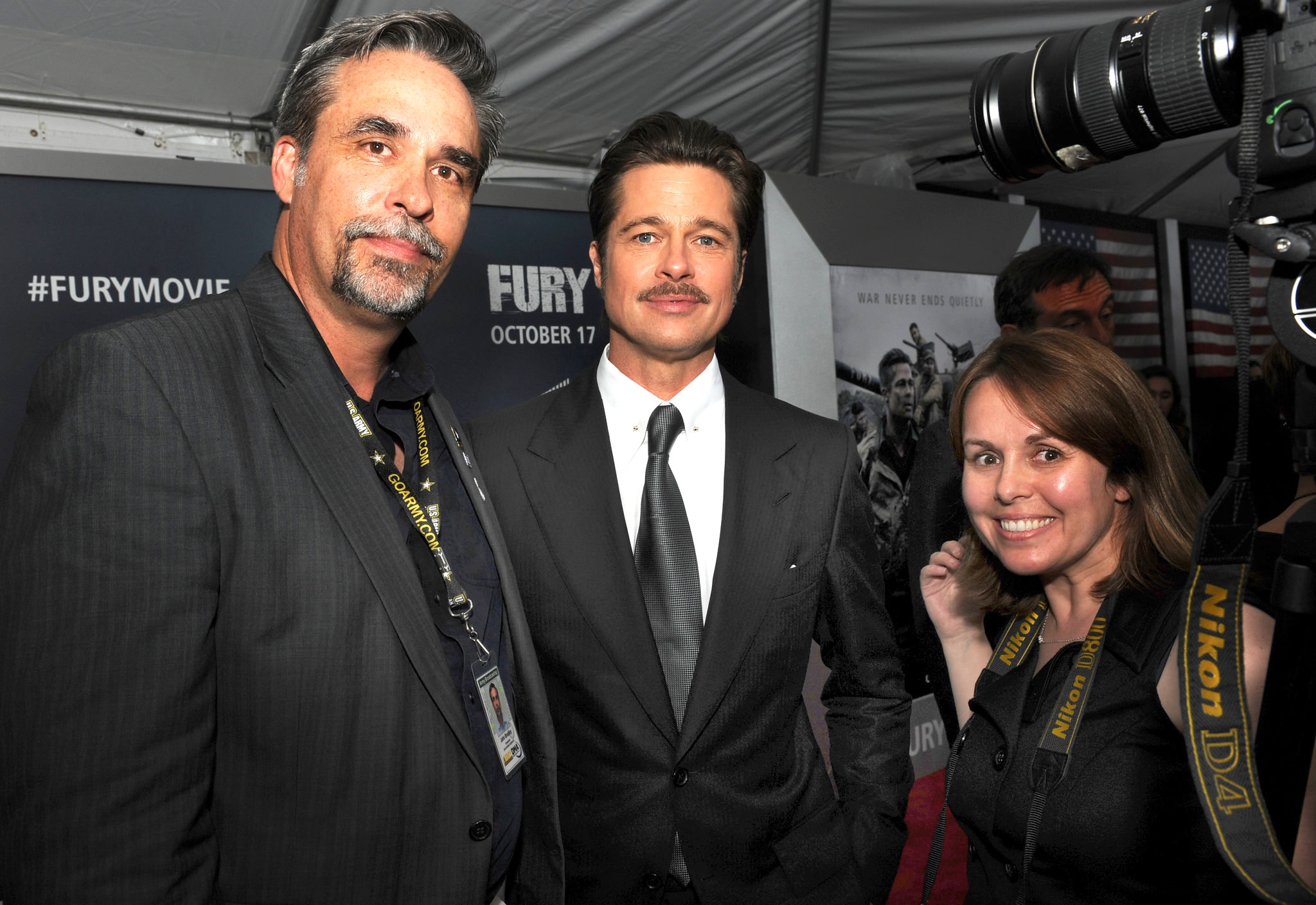

Actor Brad Pitt, center, flanked by employees of the Pentagon’s Defense Media Activity, during the world premiere at the Newseum in Washington D.C. of the 2014 movie Fury, about the U.S. Army in World War II. (Department of Defense, Marvin Lynchard, Public domain)

The alleged need to contain the Soviet threat provided an argument for U.S. government planners, notably Paul Nitze in National Security Council Paper 68, or NSC-68, to renew and expand the U.S. arms industry, which had the political advantage of putting a decisive end to the economic depression of the 1930s.

Nazi collaborators throughout Eastern Europe could be welcomed in the United States, where intellectuals became leading “Russia experts.” In this way, Russophobia was institutionalized, as old-school WASP diplomats, editors and scholars who had nothing in particular against Russians made way to newcomers with old grudges.

Among the old grudges, none were more vehement and persistent than that of the Ukrainian nationalists from Galicia, the far west of Ukraine, whose hostility to Russia had been promoted during the time that their territory was ruled by the Habsburg Empire. Fanatically devoted to denying their divided country’s deep historic connection to Russia, Ukrainian ultra-nationalists were nurtured for decades by the C.I.A. in Ukraine itself and in the large North American diaspora.

[See: Using Ukraine Since 1948]

We saw the culmination of this process when the talented comedian Volodymy Zelensky, in his greatest role as tragedian, claimed to be “the heir to the Normandy” invasion and described Russian President Putin as the reincarnation of Adolf Hitler, out to conquer the world — already an exaggeration for Hitler, who mainly wanted to conquer Russia. Which is what the U.S. and Germany apparently want to do today.

Alliance Reversal No. 3: Germany

While the Russians and Anglo-Americans joined in condemning the very top Nazi leaders at the Nuremberg trials, denazification proceeded very differently in the respective zones occupied by the victorious powers.

In the Federal Republic established in the Western zones, very few officials, officers or judges were actually purged for their Nazi past. Their official repentance centered on persecution of the Jews, expressed in monetary compensation to individual victims and especially to Israel.

While immediately after the war, the war itself was considered the major Nazi crime, over the years the impression spread through the West that the worst crime and even the primary purpose of Nazi rule had been the persecution of the Jews.

The Holocaust, the Shoah were names with religious connotations that set it apart from the rest of history. The Holocaust was the unpardonable crime, acknowledged by the Federal Republic so emphatically that it tended to erase all others. As for the war itself, Germans could easily consider it their own misfortune, since they lost, and limit their most heartfelt regret to that loss.

It was not Germans but the American occupiers who determined to create a new German army, the Bundeswehr, safely ensconced in an alliance under U.S. control. Germans themselves had had enough. But the Americans were intent on solidifying their control of Western Europe through the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

NATO’s first secretary general, Lord Ismay – who had been Churchill’s chief military assistant during World War II – succinctly defined its mission: “to keep the Americans in, the Russians out, and the Germans down.”

Nato Secretary General Lord Ismay in Chaillot’s Palace, Paris, 1953. (NATO, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The United States government wasted no time in selecting qualified Germans for their own alliance reversal. German experts who had gathered intelligence or planned military operations against the Soviet Union on behalf of the Third Reich were welcome to continue their professional activities, henceforth on behalf of Western liberal democracy.

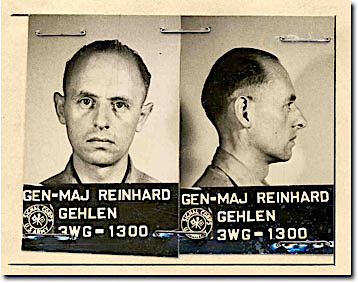

This transformation is personified by Wehrmacht Major General Reinhard Gehlen, who had been head of military intelligence on the Eastern Front. In June 1946, U.S. occupation authorities established a new intelligence agency in Pullach, near Munich, employing former members of the German Army General Staff and headed by Gehlen, to spy on the Soviet bloc.

The Gehlen Organization recruited agents among anti-communist East European émigré organizations, in close collaboration with the C.I.A. It employed hundreds of former Nazis. It contributed to the domestic West German political scene by hunting down communists (the German Communist Party was banned).

The Gehlen Organization’s activities were put under the authority of the Federal Republic government in 1956 and absorbed into the Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND or Federal Intelligence Service), which Gehlen led until 1968.

Gehlen in undated photo. (US Army, Signal Corps, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

In short, for decades, under U.S. occupation, the Federal Republic of Germany has fostered the structures of the Alliance Reversal, directed against Russia. The old pretext was the threat of communism. But Russia is no longer communist. The Soviet Union surprisingly dissolved itself and turned to the West in search of lasting peace.

In retrospect, it becomes crashingly clear that the “communist threat” was indeed only a pretext for great powers seeking more power. More land, more resources.

The Nazi leader Adolf Hitler, like the Anglo-American liberals, looked at Russia in the way mountain-climbers proverbially look at mountains. Why must you climb that mountain? Because it’s there. Because it’s too big, it has all that space and all those resources. And oh yes, we must defend “our values”.

It’s nothing new. The dynamic is deeply institutionalized. It’s just the same old war, based on illusions, lies and manufactured hatred, leading us to greater disaster.

Is it too late to stop?

Diana Johnstone was press secretary of the Green Group in the European Parliament from 1989 to 1996. In her latest book, Circle in the Darkness: Memoirs of a World Watcher (Clarity Press, 2020), she recounts key episodes in the transformation of the German Green Party from a peace to a war party. Her other books include Fools’ Crusade: Yugoslavia, NATO and Western Delusions (Pluto/Monthly Review) and in co-authorship with her father, Paul H. Johnstone, From MAD to Madness: Inside Pentagon Nuclear War Planning (Clarity Press). She can be reached at diana.johnstone@wanadoo.fr

No comments:

Post a Comment