Click here for Exit the Cuckoo's Nest's posting standards and aims.

Click here to sign the People's Proclamation and send it to everyone you know.

Source: Winter Oak

TURNING OUR BACKS ON THE LEFT-RIGHT RACKET

Paul Cudenec’s latest piece for the organic radicals website looks at the ideas of Jacques Camatte

“Revolution will make itself felt in the destruction of all that is most ‘modern’ and ‘progressive’”

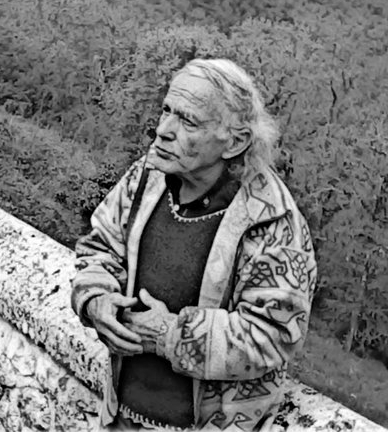

Jacques Camatte (1935-) is a political philosopher who rejects both marxism and industrial capitalism and has influenced the green anarchist movement in the USA.

Writes Alex Trotter, who edited a collection of his essays: “Camatte advocates regeneration of nature through the end or radical curtailment of civilization and technology, and a new way of life outside the capitalist/socialist mode of production”. [1]

Camatte himself insists: “The human being is dead. The only possibility for another human being to appear is our struggle against our domestication, our emergence from it”. [2]

Originally involved with the International Communist Party, and influenced in particular by Amadeo Bordiga, Camatte has over many decades forged a very particular philosophy.

Notably through the review Invariance, he has kept his thinking distinct from what might appear to be the similar strands of thought from the Situationists or the Frankfurt School, although he does refer approvingly to organic radical inspiration Ferdinand Tönnies. [3]

Like many in France, Camatte started to question marxism about the time of the 1968 worker-student uprising, explains Trotter. [4]

He came to see that the much-idolized proletariat was very much part of capital’s all-embracing system, as were the various “radical” political groups.

Writes Camatte, with Gianni Collu: “All forms of working-class political organization have disappeared. In their place, gangs confront one another in an obscene competition, veritable rackets rivaling each other in what they peddle, but identical in their essence”. [5]

Even informal groups become rackets, he says, with recruits inevitably conforming to an agenda and outlook set by influential individuals.

“What maintains an apparent unity in the bosom of the gang is the threat of exclusion. Those who do not respect the norms are rejected with calumny; and even if they quit, the effect is the same”. [6]

“Each gang of the left or the right carves out its own intellectual territory: anyone straying into one or the other of these territories is automatically branded as a member of the relevant controlling gang”. [7]

“The critique of capital ought to be, therefore, a critique of the racket in all its forms… The theory which criticizes the racket cannot reproduce it”. [8]

For Camatte, hope lies not in political revolution but in deserting the system: “We must abandon this world dominated by capital, which has become a spectacle of beings and things”. [9]

Humans in the West have been “domesticated by capital” [10] since the 19th century, he says, and we need a deep-rooted turning away from its full-spectrum control.

“Our revolution as a project to reestablish community was necessary from the moment that ancient communities were destroyed”. [11]

He envisages “the destruction of urbanization and the formation of a multitude of communities distributed over the earth”, [12] with the creation of “a world where all the biological potentialities can finally develop”. [13]

Camatte writes: “A species in harmony with nature is needed”. [14] “The global human community can only exist on the basis of multiple and diverse communities, founded upon the specific historical and geographical foundations of each zone”. [15]

All this requires a vision vastly broader that the narrowly-restriced ideological terrain usually defined as acceptable by the left.

“The reader should not be astonished if to support this amplitude we refer to authors classically tagged religious, mystical, etc” [16] he writes, in view of the fact that “capital is fundamentally a profanation of the sacred”. [17]

He argues that “the left-right dichotomy” has ceased to matter because “in one way or another they each defend capital equally”. [18]

“All the movements of the left and right are functionally the same inasmuch as they all participate in a larger, more general movement toward the destruction of the human species”. [19]

Camatte identifies the way in which the ongoing encroachment of capitalist development needs to destroy the barriers represented by “traditional social relations and previous ways of life, including previous ways of thinking”. [20]

“The species is being restructured in order that the despotic community of capital can be imposed and realized”. [21]

And he has particularly condemned marxist enthusiasm for industrial drudgery, the “capitalization of human beings” [22] in which people are “all slaves of capital” [23] and accordingly reduced to the dehumanised status of “workers”.

Trotter explains that, for Camatte, “when human beings are seen primarily as producers and laborers, they become nothing but the activity of capital”. [24]

Camatte warns that marxism is, in fact, “a theory of development”, [25] aiming for a mere “transition” [26] into “a new mode of production where productive forces blossom”. [27]

“Communism was affirmed in opposition to bourgeois society, but not in opposition to capital”. [28]

He says that with the Bolshevik revolution in Russia, the limited “revolt of the proletariat” ultimately “aided capital in its movement toward real domination” [29] by reshaping – resetting! – society to suit the needs of its own production.

“We have got to remember that capital, as it constantly overthrows traditional patterns of life, is itself revolution.

“This should lead us to think again about the nature of revolution and to realize that capital is able to take control of social forces in order to overthrow the established order in insurrections directed against the very society that it already dominates”. [30]

In a key passage very much representing the organic radical outlook, Camatte writes: “Revolution can no longer be taken to mean just the destruction of all that is old and conservative, because capital has accomplished this itself.

“Rather it will appear as as a return to something (a revolution in the mathematical sense of the term), a return to community, though not in any form that has existed previously.

“Revolution will make itself felt in the destruction of all that is most ‘modern’ and ‘progressive’ (because science is capital).

“Another of its manifestations will involve the reappropriation of all those aspects and qualities of life that have still managed to affirm that which is human”. [31]

Decades before the full emergence of the “woke” phenomenon, Camatte identified a “disintegration of consciousness” on the left caused by a splintering of any overall critique of the system into narrow campaigning for particular minority causes.

Notes Trotter: “All of these movements grouped around partial demands have lent themselves easily to recuperation by capital’s material community”. [32]

In the 1970s Camatte was already condemning leftists who supported “progressive” technology such as artificial reproduction, the precursors of today’s transgender/transhumanist cultists.

“They are unable to see that a scientific solution is a capitalist solution, because it eliminates humans and lays open the possibility of a totally controlled society”, he said. [33]

“These people seem to believe in solving everything by mutilation. Why not do away with pain by eliminating the organs of sensitivity? Social and human problems cannot be solved by science and technology. Their only effect when used is to render humanity even more superfluous”. [34]

He astutely warned in 1973, long before online education was possible: “Teachers and professors are, from the point of view of capital, useless beings who will tend to be eliminated in favour of programmed lessons and teaching machines”. [35]

Although Camatte has declared it “increasingly imbecile to proclaim oneself a marxist”, [36] one of the elements he has retained from Karl Marx’s thinking is the term Gemeinwesen, meaning the human essence, the common being of the human species, similar to the idea of “withness”.

He writes: “The separation of the human being from the community (Gemeinwesen) is a despoliation. The human being as a worker has lost a mound of attributes that formed a whole when he was related to his community”. [37]

“The human being is an individuality and a Gemeinwesen. The reduction of the human being to his present inexpressive state could take place only because of the removal of Gemeinwesen, of the possibility for each individual to absorb the universal, to embrace the entirety of human relations within the entirety of time”. [38]

Video link: Entretien avec Jacques Camatte: Errance de l’humanité, 2022 (2hrs 44 mins)

[1] Alex Trotter; ‘Introduction’, Jacques Camatte, This World We Must Leave and Other Essays, ed. Alex Trotter (New York: Autonomedia, 1995), p. 9. All following page references are to this work.

[2] Jacques Camatte, ‘The Wandering of Humanity’ (1973), p. 88.

[3] Camatte, ‘Against Domestication’ (1973), p. 96.

[4] Trotter, ‘Introduction”, p.8.

[5] Jacques Camatte & Gianni Collu, ‘On Organization’ (1972), p. 26.

[6] Camatte & Collu, ‘On Organization’, p. 29.

[7] Camatte, ‘Against Domestication’, p. 96.

[8] Camatte & Collu, ‘On Organization’, p. 32.

[9] Camatte, ‘The World We Must Leave’ (1976), p. 170.

[10] Camatte, ‘The Wandering of Humanity’, p. 48.

[11] Camatte, ‘The Wandering of Humanity’, p. 71.

[12] Camatte, ‘The Wandering of Humanity’, p. 66.

[13] Camatte, ‘The Wandering of Humanity’, p. 70.

[14] Camatte, ‘The World We Must Leave’, p. 156.

[15] Camatte, ‘Echoes of the Past’ (1980), p. 204.

[16] Camatte, ‘The Wandering of Humanity’, p. 73.

[17] Camatte, ‘Echoes of the Past’, p. 197.

[18] Camatte, ‘Against Domestication’, pp. 94-95.

[19] Camatte, ‘Against Domestication’, p. 95.

[20] Camatte, ‘Against Domestication’, p. 111.

[21] Camatte, ‘Echoes of the Past’, p. 207.

[22] Camatte, ‘The Wandering of Humanity’, p. 40.

[23] Camatte, ‘The Wandering of Humanity’, p. 68.

[24] Trotter, ‘Introduction’, pp. 13-14.

[25] Camatte, ‘The Wandering of Humanity’, p. 77.

[26] Camatte, ‘The Wandering of Humanity’, p. 77.

[27] Camatte, ‘The Wandering of Humanity’, p. 86.

[28] Camatte, ‘The Wandering of Humanity’, p. 47.

[29] Camatte, ‘Against Domestication’, p. 112.

[30] Camatte, ‘Against Domestication’, pp. 112-13.

[31] Camatte, ‘Against Domestication’, p. 113.

[32] Trotter, ‘Introduction’, p. 12.

[33] Camatte, ‘Against Domestication’, p. 94.

[34] Camatte, ‘Against Domestication’, p. 93.

[35] Camatte, ‘Against Domestication’, p. 111.

[36] Camatte, ‘The Wandering of Humanity’, p. 70.

[37] Camatte, ‘The Wandering of Humanity’, p. 64.

[38] Camatte, ‘The Wandering of Humanity’, p. 69.

No comments:

Post a Comment