Click here for Exit the Cuckoo's Nest's posting standards and aims.

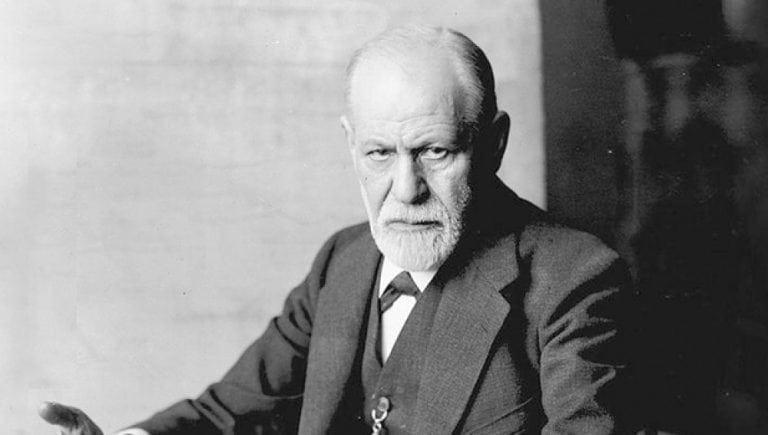

What’s Wrong with Sigmund Freud?

Originally published on Thu, Jul 2, 2015

First published in Socialist Review

[dropcap]S[/dropcap]igmund Freud was a creative thinker and a prolific writer who continues to shape our views of human behaviour. While academics debate Freud’s ideas in the abstract, with no regard for consequences, socialists consider everything in social context. Does Freud’s influence benefit or block the cause of the working class and the progress of humanity?

Mental illness raises the question of how society should respond to its wounded members. Should they be held individually responsible or socially supported? The answer depends on the balance of class forces. The capitalist class denies experience and blames its victims, while working-class rebellions validate experience and demand support for the wounded.

On which side of the class line do Sigmund Freud and his theories belong? Freud began his career as an advocate for the oppressed during a time of working-class revolt. As the capitalist class gained strength, he switched sides to serve the oppressors.

Background

Every social rebellion brings lived experience to the fore to be rediscovered by middle-class professionals. The 1871 Paris Commune had a profound impact on Jean-Martin Charcot, a neurologist working at a Paris asylum for the sick, destitute, and victims of violence. Such patients were traditionally dismissed as raving lunatics. Rejecting tradition, Charcot listened to his patients, inquired about the events in their lives, and concluded that mental illness is a response to traumatic experience.

Charcot’s student, Pierre Janet, identified ‘dissociation’ as the means by which traumatic events cause mental illness. According to Janet, experiences that are too traumatic to be integrated into conscious awareness are dissociated or split off and held in what he called ‘the subconscious.’ These disconnected fragments of experience periodically intrude into conscious awareness as frightening thoughts, images, sensations, and physical symptoms. Patients’ efforts to manage their distress lead to secondary symptoms including addictions, obsessions, compulsions, self-destructive behaviors, and violence. Some sufferers are so engulfed by their symptoms that they lose contact with the external world.

The trauma model of mental illness was well-received. Five conferences on dissociation were held in 1890 alone, and Janet was invited to deliver a series of lectures at Harvard Medical School. Distinguished scientists flocked to Paris. One of them was 29-year-old Viennese physician Sigmund Freud, who joined Charcot’s team in 1885.

Children

By the 1860s, the sexual abuse of children was well documented by the French courts. Forensic physicians, who examined live children and autopsied dead ones, testified that most claims of sexual assault against children could be verified by medical evidence.

Despite the evidence, conservatives like Alfred Fournier refused to believe that so many children were being victimized. In his 1880 address to the Academy of Medicine, Fournier urged physicians to view a child’s report of sexual assault as a symptom of pseudologica phantastica – a pathological fiction or fantasy. Claude Etienne Bourdin and Paul Brouardel echoed Fournier to insist that children’s reports of sexual assault were “pathological lies” originating in the “evil instinct of hateful children.”

Proving that we see what we believe, Fournier stated, “I have come across, in my practice, large numbers of vaginal inflammations which appeared in young children in an absolutely spontaneous manner, apart from any criminal violence, apart from any possibility of sexual assault.” He added that men accused of sexually assaulting children are, “all too often excellent and perfectly honourable…absolutely incapable of ignominious action,” a view that resonated favorably with the patriarchs of the time.

The class lines were drawn between those who accepted the evidence of child victimization in the family and those who denied it in order to defend the family.

Initially, Freud accepted the reality of child abuse. His early papers (1893-1896) embraced the importance of trauma and the mechanism of dissociation. While Charcot believed that any kind of trauma could cause mental illness, Freud was more specific. In Heredity and the Aetiology of Neurosis (1896), he wrote, “a precocious experience of sexual relations…resulting from sexual abuse committed by another person…is the specific cause of hysteria…not merely (as Charcot had claimed), an agent provocateur.” He added that patients hide or repress memories of childhood sexual assault to protect their families.

Transition

The decades marking the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century saw the capitalist class and the working class locked in battle, with neither able to strike a decisive blow. As the balance of class forces swung back and forth, Freud also vacillated.

Despite his initially courageous stance, Freud was deeply troubled by the extent of incest in the family. Back in Vienna, his colleagues were appalled that Freud was exposing the family as a center of sexual oppression and indirectly indicting a society that required such a family structure.

Facing professional isolation and possible career death, Freud recanted the following year, writing, “it was hardly credible that perverted acts against children were so general.” In An Autobiographical Study (1925), he reflected:

I believed those stories [of childhood sexual trauma] and consequently supposed that I had discovered the roots of the subsequent neurosis in these experiences of sexual seduction in childhood. If the reader feels inclined to shake his head at my credulity, I cannot altogether blame him…I was at last obliged to recognize that these scenes of seduction had never taken place, and that they were only fantasies which my patients had made up. (p.34)

Freud’s conversion was not decisive. When WWI revived the importance of trauma in causing mental breakdown, Freud publically defended shell-shocked soldiers who had been charged with malingering. However, as he acknowledged in The History of the Psycho-Analytic Movement (1914), the trauma model and psychoanalysis are incompatible. He had to choose whether mental breakdown is caused by external events or internal conflict.

In The Assault on Truth: Freud’s Suppression of the Seduction Theory (1984), Jeffrey Masson documents Freud’s process of conversion from courageous supporter of child victims to career-building opportunist.

Freud not only joined the skeptics who dismissed child victims, he provided them with pseudoscientific ammunition. Standing reality on its head, he insisted that reports of childhood sexual assault represent a normal yet disguised sexual desire for the parent of the opposite sex. Freud’s ‘Oedipus complex’ cast the child as the seducer and normalized the despicable practice of adults ‘initiating’ children into sex under the guise of assisting their maturation.

Choosing psychoanalysis made Freud a wealthy celebrity. Before the 20th century, psychiatry was largely restricted to the treatment of patients in insane asylums. With The Psychopathology of Everyday Life (1901), Freud shattered the barrier between mental illness and normal behavior by proposing that commonplace occurrences (slips of the tongue, what people forget, and the mistakes they make) indicate repressed sexual feelings that can generate anti-social behaviors unless they are treated. Between 1917 and 1970 the proportion of psychiatrists practicing outside institutions swelled from 8 to 66 percent.

Reaction

Times of revolt favour views of mental illness that emphasize external factors. After the defeat of the Russian Revolution, the epoch of reaction favoured views of mental illness that emphasize internal factors.

Psychiatry partnered with the law to impose social control. Psychiatrists used pseudoscientific labels like ‘pathological lying,’ ‘hysteria,’ and ‘genital hallucinations’ to discredit the validity of child testimony. The legal image of the child as “the most dangerous of all witnesses,” mirrored the psychiatric image of the child as cunning, vengeful, and disturbed. As one prominent psychiatrist pleaded, “When are we going to give up, in all civilized nations, listening to children in courts of law?”

Freud’s biological determinism contributed to the reaction. In Civilization and Its Discontents (1930), he wrote, “the psychological premises on which the system (of communism) is based are an untenable illusion” because “nature, by endowing individuals with extremely unequal physical attributes and mental capacities, has introduced injustices against which there is no remedy.”

While marxists celebrate the social nature of human beings, Freud saw human beings as innately aggressive, so he feared mass democracy. In Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego (1921), he wrote that being in a crowd overrides the social constraints that keep animal instincts under control. And in The Future of an Illusion (1927), he warned, “these dangerous masses must be held down most severely and kept most carefully away from any chance of intellectual awakening.”

Virtually all research into childhood trauma ceased, and doctors were warned not to believe patient reports of childhood sexual assault. As late as 1975, the Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry(U.S.) estimated the frequency of incest as one case per million.

While psychiatry turned its back on child victims, sociology rediscovered them in the 1950s. The Kinsey national surveys on American sexuality revealed that 20 to 33 percent of women reported a childhood sexual encounter with an adult male and 10 percent reported father-daughter incest. However, Freud cast a long shadow, and Kinsey argued that such “encounters” were not harmful in themselves, but were made harmful by prudish and punitive social reactions.

At the time, psychology studies offered two options: one studied Freud to learn how to use Freudian metaphors to interpret people’s experiences, or one studied behaviourism to learn how to manipulate human behaviour with no regard for the mind.

1960s

The mass struggles that peaked in the late 1960s revived the importance of lived experience and resurrected the trauma model of mental illness. Veterans of America’s war in Vietnam demanded acknowledgment and treatment for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). The women’s liberation movement demanded that child abuse and women’s oppression be recognized as major social problems.

A new generation of women physicians and psychiatrists defied their superiors’ instructions and began to take seriously what their patients were saying. Groundbreaking books like Judith Lewis Herman’s Father-Daughter Incest (1981) expanded on the trauma model to explain why adult-child sex is so damaging: the betrayal of the adult’s protective role; the powerlessness of the child to resist or escape; the sexual objectification of the child; the child’s need to distort reality and sense-of-self to accommodate the abuse; and society’s denial of the child’s experience.

Facing mounting pressure, the American Psychiatric Association included a limited definition of PTSD in its 1980 edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). There followed a flood of research into the prevalence and psychological impact of trauma.

The psychiatric establishment pushed back. Despite mounting evidence that most people labelled with DSM disorders have trauma histories and that past trauma magnifies the risk of mental illness, no amount of proof has been enough to restructure the DSM. Doing so would expose social factors as the prime cause of mental illness. Consequently, PTSD remains the only DSM disorder that is attributed to external events, and DSM population surveys still do not include a trauma history. By 1996, the entire world literature contained only one published controlled pharmacological study of the treatment of children suffering from PTSD.

Backlash

In the 1970s, the capitalist class launched an offensive to retake lost ground. The economic assault on workers’ organizations, wages, benefits, and conditions was accompanied by virulent victim-blaming. Sick people were blamed for making bad choices. Injured workers were blamed for not working safely. Welfare recipients were portrayed as lazy cheats. Affirmative action and the right to abortion came under attack.

As the balance of forces shifted in favour of the capitalist class, the deniers of child abuse grew more confident. In 1992, Pamela and Peter Freyd founded the False Memory Syndrome Foundation after their daughter (with the support of her grandmother and uncle) accused her father of childhood sexual assault.

Building on Fournier and Freud’s legacies, the Foundation coined the term, ‘false-memory syndrome,’ which it claims results when therapists plant false memories of childhood sexual assault in the minds of gullible patients. ‘False-memory syndrome’ is used the same way that Fournier’s pseudologica phantastica and Freud’s Oedipus complex are used – to deny the validity of claims of child sexual victimization and to advocate on behalf of the accused.

During the 1990s, debates over ‘false-memory syndrome’ dominated the American mass media despite the fact that a 1991 national survey had revealed 129,697 confirmed child victims of sexual assault and a Los Angeles survey estimated that one in four American women and one in six men had been sexually assaulted as children.

Skeptics who defend the status quo typically dominate public discussion. Acknowledging child victims threatens to expose the institution of the family and the system that it serves. The deniers of child abuse counter that threat. Even though the DSM has never acknowledged ‘false-memory syndrome,’ public mental-health advisories typically include a caution not to take reports of child sexual assault at face value.

Context

Some say that Freud contributed to our understanding of the mind. However, nothing human can be understood in the abstract. Marxists interpret thoughts, feelings, and behaviours in their social context. Freud interpreted thoughts, feelings, and behaviours according to his personal opinion of what they represent.

Those who seek to reconcile Marx and Freud skirt a central contradiction: For marxists, labour is the basic condition for human existence. For Freud, sex is more important. Misguided support for Freud blocks an understanding of the mind that is rooted in social labour.

It is impossible to integrate marxism and psychoanalysis, because marxism serves the working-class while psychoanalysis and its derivatives serve the capitalist class. Just as Freud refused to believe his patients’ reports of childhood trauma, the capitalist class refuses to acknowledge the traumatic legacy of slavery and the ongoing trauma caused by imperialism, war, oppression and exploitation.

Freud’s legacy continues to cause misery for countless victims of capitalism who are discredited and re-victimized by his theories. It is not sufficient to expose Freud; we must also eliminate the system that created him.

I am a physician and a socialist. I always wanted to be a doctor, probably because my brother Ron was born with severe hemophilia for which there was no treatment at the time. To my young mind, doctors had the power to stop suffering, and I wanted that power.

I had the good fortune to be born at the right time. During the 1960s, the Canadian government subsidized children from the working class to go to university. My second stroke of luck was getting into medical school.

I soon discovered how powerless doctors really are. Most of my patients’ problems were rooted in social conditions that were outside my control. The best I could do was manage their symptoms.

Medicine radicalized me. I was a socialist because I came from a family of socialists. But I didn’t really understand capitalism. Like most people, I thought it was an economic system. —Susan Rosenthal.

Source: The Greanville Post

No comments:

Post a Comment